Universalization and Parochialization:

Redfield’s Great and Little Traditions concept explains the contents of traditions present in a civilization that are inter-dependent and interactive. The process of that interaction and how the two traditions affect each other is well explained by Mckim Marriott’s concept of Universalization and Parochialization. Parochialization denotes the downward spread into the parochial village culture of elements from Sanskritic Hinduism (Great Tradition). Universalization is the converse upward spread of elements of village culture (Little Tradition) into Sanskritic Hinduism.

The mixture of elements in Hindu tradition has been going on from the earliest times and has resulted in a form of society and culture in which interactions of Little and Great Traditions has become endemic and stable. The patterns of this interaction, and the media through which it is sustained, have been identified with marriage, trade, religious festivals and pilgrimages, public administration, as well as activities of itinerant entertainers, bards, genealogists and holy men. The flow of reciprocal influence between Great and Little Tradition, or “higher” and “lower” levels of Hinduism is mainly channelled through such media.

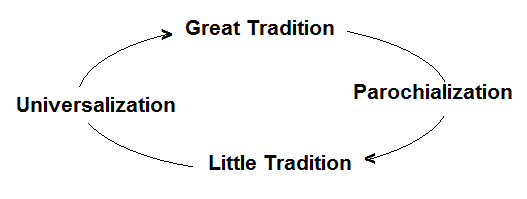

In his study of Kishangarhi village in Uttar Pradesh, Mckim Marriot used the festivals and deity as media of this interaction, to explain the twin process of Universalization and Parochialization. In a diagrammatic form, the two can be shown as follows-

In Kishangarhi, the elements of both Sanskritic tradition and local culture are present in close adjustments and integration, as far as religion is concerned. Out of nineteen festivals celebrated at Kishangarhi, only fifteen are sanctioned in universal Sanskritic texts, which themselves form a very small part of the entire body of festivals sanctioned by Sanskritic literature. The villagers are confused or choose between various classical meanings for their festivals. And even the most Sanskritic of the local festivals have incorporated elements of ritual that arose out of the local peasant life.

Speaking of Universalization, Marriott thinks that the little traditions of the folk exercise their influence on the authors of Hindu great tradition who take up some elements of belief or practice, incorporate it in the philosophical Hinduism, and thus universalize that element by their teachings- oral or textual. Marriott suggests that the Goddess Lakshmi of Hindu Great Tradition is derived from such deities as he saw represented in Kishangarhi fashioned in images of dung. The nature and meaning of both are similar and the villagers identify the local images as Lakshmi. Another local annual festival, which Marriott considers an example of Universalization, is in which women go to their brothers to express their attachment by placing barley shoots on their brother’s heads and ears. The brothers reciprocate with gifts on the same day, as per classic Sanskritic tradition, the village priest the wrist of his patrons with coloured thread and get gifts in return. Marriott considers both as examples of Universalization.

The opposite process, the parochialization, is shown by Marriott through the following two instances. Sanskritic traditions sanction an annual festival Dussehra in honour of a great goddess of the Great Traditional Hindu pantheon, Durga. In Kishangarhi people include a diety, ‘Naurtha‘, who is worshipped in the morning and evening for nine days, and represented by figurines of mud. This deity has no place in the great tradition and had come into being as a linguistic corruption of nauratra (nine nights), associated with the Dussehra festival. By mere linguistic confusion in the communication between little and great tradition, he concludes, a minor goddess has been created. Another instance of parochialization is the existence of a stone in Kishangarhi, which is worshipped by the bride and bridegroom. This stone is supposed to represent venus, a divine sage of the Sanskritic traditions as informed by the Brahmin elders in the village. The origin of the stone is forgotten and is now regarded as the abode of ancestral spirits of the Brahmins who put it there. “Parochialization is a process of localization of limitation upon the scope of intelligibility of deprivation of literary form, of reduction to less systematic and less reflective dimensions. The process of parochialization constitutes the characteristic creative work of little communities within India’s indigenous civilization”.

Though the concept of universalization and parochialization may be useful as an analytical model, its empirical utility is doubtful, for the simpler reason that it is very difficult to establish the origin or spread of any “Parochial” element without a thorough historical study of each element. Moreover, the concept takes into account only orthogenetic processes of change, while the revolutionizing influence of communication and media (newspapers, periodicals, radio, cinema etc.) have been ignored.

Singh (1977) points out that the concept, particularly the universalization process, is anticipated by Srinivas concept of Sanskritization which explains the adoption of Sanskritic tradition by tribes to become a caste and by lower-order castes to achieve a higher status.

Comments (No)